Here are some questions people often have. Click on each question to expand the section.

About the thyroid and thyroid cancer

What is the function of the thyroid gland?

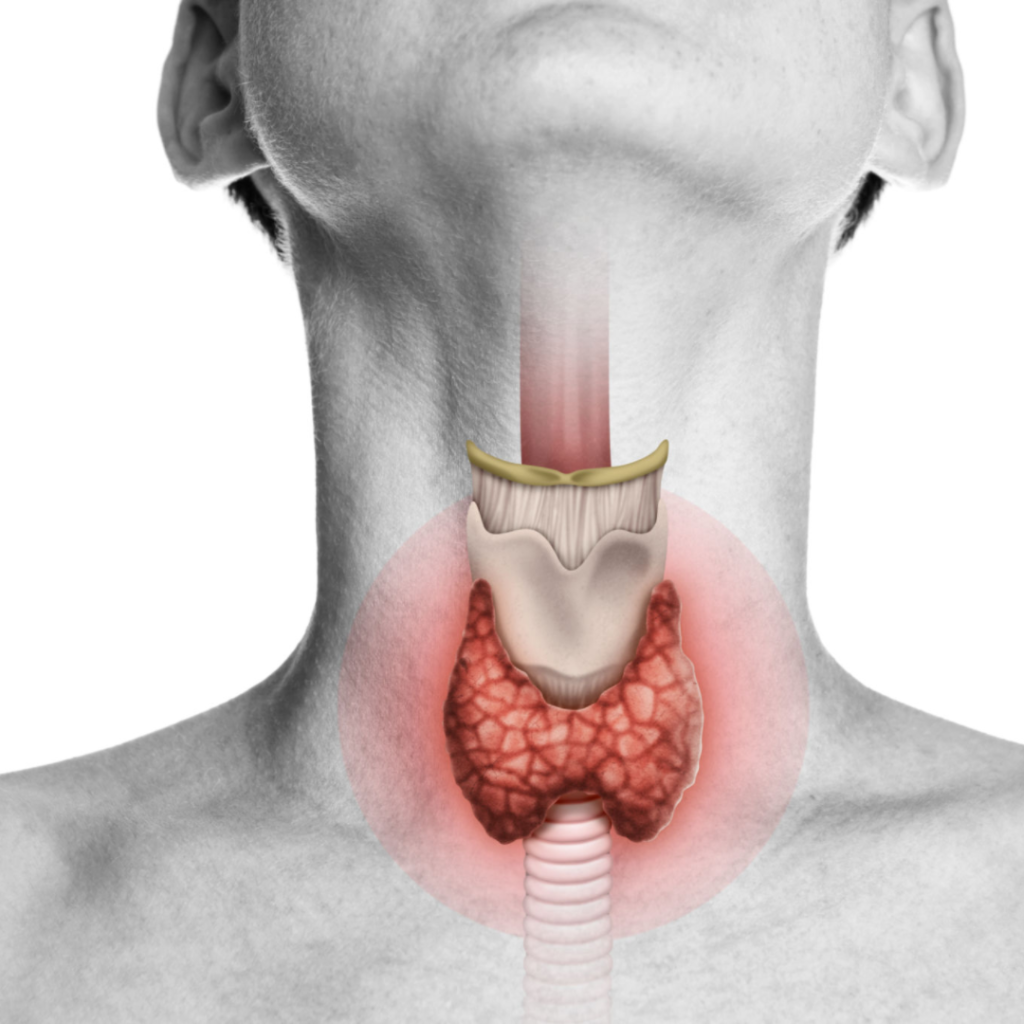

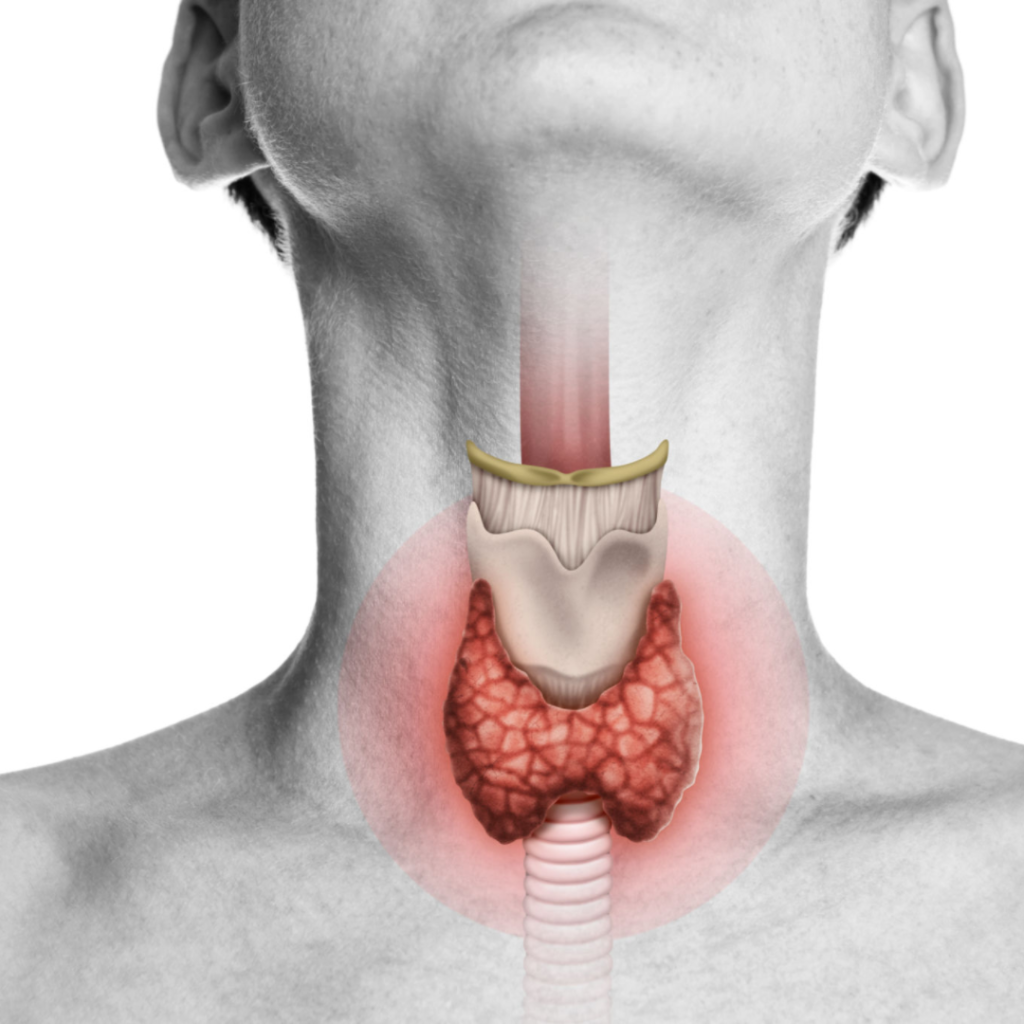

The thyroid gland is a butterfly shaped organ that lies in the front of the neck. The right and left halves (called lobes) are each normally the size of your thumb, and lie next to the trachea (windpipe). The two halves are connected by a small amount of thyroid tissue in front of the windpipe (called the isthmus).

The thyroid gland is responsible for making thyroid hormone. This is its only job. Thyroid hormone regulates the metabolism of all the cells in your body. The production of thyroid hormone can be measured with a simple blood test called TSH.

Thyroid hormone can be taken in tablet form if your thyroid is not producing enough thyroid hormone (called thyroxine, or levothyroxine). By measuring TSH levels in blood, your doctor can ensure that you are receiving enough thyroid hormone replacement. By taking thyroxine, the function of your thyroid can be safely and effectively replaced by tablets.

What is thyroid cancer?

Thyroid cancer occurs when the cells of the thyroid stop producing thyroid hormone and begin to grow in an abnormal manner. Some things can increase the chance of this (such as prior radiation exposure to the neck, or a family history of thyroid cancer), but most people do not have a risk factor or a reason that the cancer occurred.

Most thyroid cancers grow slowly, and usually remain within the thyroid gland for extended periods. If spread outside the thyroid occurs, this usually occurs to the lymph nodes just around the thyroid. This can usually be detected by an ultrasound scan.

A ‘low-risk’ thyroid cancer will be one that is small (usually less than 2-3cm in size), completely within the thyroid gland, and without evidence of spread to lymph nodes.

Why do people get thyroid cancer?

Thyroid nodules (lumps) are extremely common, and mostly they are benign (non-cancerous).

Thyroid cancer can occur at any age and usually there is no particular reason identified why it developed.

Some things can increase the chance of thyroid cancer developing, particularly exposure to radiation in childhood (eg radiotherapy for another childhood cancer, exposure to radiation from nuclear power plant accidents). There are some uncommon genetic syndromes that can increase the chance of thyroid cancer (eg familial polyposis, Carney complex, Multiple endocrine neoplasia 2, Cowden Syndrome). Sometimes thyroid cancer can also run in families.

What is a ‘low-risk’ thyroid cancer?

- A low-risk thyroid cancer is one that :

- Has a low chance of spreading beyond the thyroid gland

- Has a very low chance of coming back once it is removed (usually less than 5%, or less than a 1 in 20 chance)

- Has an extremely low chance of causing death (close to zero).

- By identifying that a thyroid cancer is ‘low-risk’, doctors and patients can choose a smaller operation, or perhaps no operation, and still effectively treat the cancer.

- Working out that a cancer is low-risk involves:

- Considering a person’s history, family history, and risk factors

- Careful examination of the ultrasound and biopsy features

- Careful examination of the cancer under a microscope if/when it has been removed

- Sometimes, doctors can only determine that a cancer is low-risk after it has been removed and examined under the microscope. This means that:

- You may be told that your cancer is likely to be a low-risk cancer before your surgery.

- However, after your surgery, there is a chance that unexpected features mean that this ‘low-risk’ classification is not appropriate.

How is low-risk thyroid cancer usually treated?

There are three treatment options for low-risk thyroid cancer

- Removing the whole thyroid gland (total thyroidectomy), or

- Removing the right or left half of the thyroid gland (right or left hemithyroidectomy), or

- Monitoring the cancer without removing it (active surveillance)

If the cancer is removed, it is examined under the microscope in the laboratory

- If the laboratory assessment confirms that it is a low-risk cancer then

- no further treatment (such as radioactive iodine or more surgery) is needed.

- no further treatment (such as radioactive iodine or more surgery) is needed.

- Monitoring blood tests (for thyroid hormone levels) and neck ultrasounds (to check all the cancer has been removed) will be recommended for a period of time.

- Occasionally, the laboratory assessment finds that it is not a low-risk cancer.

- In this case, your doctor will discuss what this means for you.

- Sometimes, additional treatment may be reccommended, such as surgery to remove the other half of the thyroid (if it is still present); or radioactive iodine.

- The good news is that even in this circumstance, the chance of the cancer coming back remains low (usually less than 10% or 1 in 10 chance), and the chance of dying of thyroid cancer is very low (less than 1%, or 1 in 100 chance).

If the cancer is not removed, it will be monitored with regular neck ultrasound every 6-12 months.

- If the cancer shows signs of growth, your doctor will discuss with you whether it should be removed.

- In most cases, the treatment outcome is the same if you have to have surgery later, rather than straight away

What is the prognosis of low-risk thyroid cancer?

Generally speaking, the chance of low-risk thyroid cancer coming back is less than 5% . This means that of 20 people with a low-risk thyroid cancer, only one person will experience a recurrence. If a recurrence occurs, it usually is detected as a small nodule in the neck. This recurrence can be treated with surgical removal, and sometimes with a dose of radioactive iodine. The long term prognosis for thyroid cancer, even after a recurrence like this, usually remains excellent.

The chance of dying from a low-risk thyroid cancer is very low, less than 1% over 10 years of follow up.

About treatments

What are the common complications of thyroid surgery (scar, tablets, voice change)?

Thyroid surgery should always be performed by an expert thyroid surgeon. This is a surgeon that commonly performs thyroid surgery for thyroid cancer. Any surgery can experience a complication, such as a reaction to a medication, infection or bleeding. The following complications are important complications unique to thyroid surgery. Please ask your surgeon for more details, and how these might specifically relate to you.

Scar

The thyroid is almost always removed through the front of the neck. This will leave a small scar. The surgeon will often place this in a skin fold, so it becomes less prominent over time.

Need for thyroid hormone tablets

If the whole thyroid is removed, then thyroid hormone tablets (thyroxine) are required to be taken for the rest of your life. These are usually started the morning after surgery.

If half of the thyroid is removed, then the other half keeps making thyroid hormone. In about 1 in 3 cases (30%), a thyroid hormone tablet will still need to be taken long term to boost thyroid hormone levels

Voice change or hoarseness

The thyroid sits just in front and below the voice box (larynx), and gently presses on it. Removing part of, or all of the thyroid can cause subtle changes in voice quality, due to changes in pressure over the voice box. Many patients notice no or minimal voice change, but when voice change occurs, it usually improved over the weeks to months following surgery.

The nerves to the voice box run behind the thyroid and are called the recurrent laryngeal nerves. There are also nerves above the thyroid (superior laryngeal nerves). If one of these nerves is damaged during surgery, patients can experience voice hoarseness, a loss of voice volume, or a change in vocal pitch. Often this will improve over time, but occasionally voice changes can be permanent. The chance of permanent damage is generally less than 2% (or a 1 in 50 chance) after total thyroidectomy.

Low calcium levels in the blood (hypoparathyroidism)

Low calcium levels in blood (hypoparathyroidism)

There are 4 parathyroid glands (2 on each side of the neck) that sit behind the thyroid and control calcium metabolism.

If all four glands are damaged at the time of thyroid surgery, calcium and strong vitamin D tablets are required. Usually, this can only occur if the whole thyroid is removed (the parathyroid glands on the other side are not affected if half the thyroid is removed).

Usually, parathyroid damage is temporary, and tablets are weaned over the course of a few weeks following surgery.

Occasionally, parathyroid gland damage can be permanent, and calcium and vitamin D tablets are required lifelong.

- The chance of this happening after a total thyroidectomy is usually 5% or less.

- The chance of this happening after hemithyroidectomy is close to 0.

Calcium and vitamin D tablets often need to be taken several times per day, and monitored by regular blood tests. Stopping these tablets suddenly can be dangerous.

Who should be involved in my care?

Thyroid surgeon:

Should be be a member of the Australian and New Zealand Endocrine Surgeons (ANZES) or the Australian Society of Head and Neck Surgeons (ASOHNS).

Your surgeon will carefully explain your condition, your treatment options, and advise you what type of treatment is required.

Endocrinologist:

Should be a member of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians and Endocrine Society of Australia.

An endocrinologist is a hormone specialist, that may have been involved in the assessment of your thyroid nodules, or may give advice on thyroid hormone or calcium levels. If you have not yet seen an Endocrinologist, your surgeon will advise you whether this is required and can make a referral if necessary.

Ultrasound Specialist:

This may be your surgeon, endocrinologist or a radiologist. They will carefully assess your neck with ultrasound to characterize and describe any nodules. This is an important part of the assessment of your thyroid nodule and helps determine if it will be low-risk. A small needle biopsy may be taken to confirm the nature of any nodules.

General practitioner:

Your general practitioner is likely to be the person that referred you for specialist management. They are an important coordinator of your care, and are usually best placed to help you understand and manage all of your health conditions.

Your general practitioner is also an important source of support through this process, and along with your specialist team, can assist you with accessing additional psychological or social supports if they are needed.

Is low-risk thyroid cancer treated with chemotherapy or radiotherapy?

No.

The initial treatment for low-risk thyroid cancer is either just to remove the lump containing cancer (by removing half or all of the thyroid gland), or by leaving the lump containing the cancer in the body and monitoring with ultrasound scans. For most people, these treatments are all that are required.

Uncommonly, the cancer can come back, or show higher-risk features. This generally occurs in less than 5% of low-risk cancers (less than a 1 in 20 chance). If this occurs, treatment with radioactive iodine is often recommended.

Might I need more surgery after a hemithyroidectomy?

If you and your doctor choose to remove only the half of the thyroid that contains the cancer, there is a chance that you may need a second operation in the future to remove the remaining half of the thyroid gland.

Usually, the reason that this additional surgery would be recommended is that your cancer had an unexpected feature when examined under the microscope that means that it could not be completely classified as a ‘low-risk cancer.

By removing the remaining half of the thyroid, you are then able to have radioactive iodine treatment, which can eliminate any remaining thyroid cells in your body (either benign or cancerous). Radioactive iodine can only be given after the whole thyroid has been removed.

The chance of needing this second surgery varies from person to person, but may typically affect around to 1 in 3 people. An Australian study discussing this issue can be found here.

What is radioactive iodine? Who is this treatment for?

Radioactive iodine is a special treatment designed to destroy any thyroid cells (benign or cancerous) in the body. It is taken as a capsule or a drink on a single occasion. The side effects are not like chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Most people experience few side effects.

For low-risk cancers radioactive iodine treatment is generally not recommended, because in most cases all the cancer has been removed, and studies have not shown a benefit of giving radioactive iodine to these people. In addition, exposing the body to a small dose of radiation can lead to a dry mouth, and has a very small risk of increasing the likelihood of other cancers in the future.

Radioactive iodine treatment is usually only recommended for cancers that are NOT low-risk cancers. Sometimes, when a cancer has been removed and examined in the laboratory, it is reclassified as a higher risk cancer. In these cases, radioactive iodine can be recommended. If only half of the thyroid has been removed a second operation to remove the remaining thyroid needs to occur before radioactive iodine can be given. The risk of removing the whole thyroid gland over two operations is no different to removal of the whole thyroid gland at the first operation, however two operations, and two recovery periods are required.

Radioactive iodine can only be administered after the whole thyroid has been removed.

Why can’t I just have radioactive iodine without surgery?

Unfortunately this doesn’t work. In order for radioactive iodine to be effective against cancer, all thyroid tissue has to be removed first. This is because normal thyroid tissue takes up much more radioactive iodine than cancer, so the treatment wouldn’t get to where it’s needed.

What about nodule ablation?

At present, ablation of cancerous nodules using thermal ablation, or microwave ablation techniques remains an experimental treatment, and should generally be conducted as part of a research study.

About symptoms I may experience

What is thyroid hormone replacement (thyroxine)? How do I take it? What are the side effects?

Thyroxine (levothyroxine) is your body’s natural thyroid hormone in tablet form. It is the main hormone made by the thyroid gland. It is taken once a day on an empty stomach (at least 30 minutes before food).

Because it is your body’s natural hormone, there are no side effects when you are given the correct dose that your body needs. To adjust the dose, a blood test is performed every 6-8 weeks until the dose is stable, checking a hormone called TSH. Once stable, you generally only need a thyroid blood test once per year.

Most people feel their usual self when taking thyroid hormone, but occasionally people don’t feel completely well. The reasons for this are not well understood, but can be worked through with your doctor.

Do people gain weight after thyroidectomy?

There are lots of potential factors that contribute to weight change in our society, so working out the reason that weight gain might occur is complex.

After having the whole thyroid removed, some weight gain is possible. In multiple studies, on average people gain 0.5-1.5kg of weight after total thyroidectomy. It’s not clear whether this only occurs in people who don’t get enough thyroid hormone replacement, or whether it’s due to other factors such as being more sedentary after an operation or changes in diet. Being aware of this means that you can be proactive with dietary and lifestyle choices after thyroid surgery to minimise the chance of this occurring. Your doctor will be proactive to ensure that you receive the correct dose of thyroid hormone, and that this is closely monitored.

Whether weight gain occurs after hemithyroidectomy or active surveillance hasn’t been well studied.

Does hair fall out because of treatment?

Losing all your hair is not a side effect of any treatment for low risk thyroid cancer.

However, when your body is under stress, particularly if there are changes in thyroid hormone levels, a ‘hair fall’ can occur. (the medical word for this is Telogen effluvium) This is where people notice more hair than usual coming out when they wash or brush it. Whilst this can be disconcerting, it will usually stabilise once the stress resolves and the thyroid hormone levels stabilise, which usually takes 6 weeks or so.

You should avoid taking supplements with high dose biotin, as these can interfere with thyroid blood tests.

Is there a thyroid diet that I should follow? What else should I do?

It is normal to want to make positive lifestyle changes to improve our health. Eating a healthy, balanced diet is important for general health. However there is no particular evidence that one diet is superior to another diet for thyroid nodules.

Some helpful information on diet and thyroid health has been provided by the British Thyroid Foundation, link here

Cancer Australia has also provided some information on diet and lifestyle for people with cancer, link here

What support is there if I am feeling anxious or depressed?

Being diagnosed with cancer can have a significant impact on mental health. It is appropriate to acknowledge this, and seek support if needed. Speaking with a trusted friend or family member, your local doctor, or your specialist can all be useful.

There are some online resources developed to support you through this experience. Click here to access resources from Cancer Australia, or resources from the Cancer Council

What to do next?

To return to review your treatment options, click here.

If you are ready to think through and process this information, with prompts to help you weigh various options, click here.

If you have suggestions regarding this site, or would like to give feedback, please click here (this will open a survey in a new window)